René Redzepi stunned the food world this week when he announced plans to close his Copenhagen restaurant, Noma, in 2024, citing the financial and emotional toll of running a restaurant that apparently can’t sell enough $800-a-head tasting menus to turn a profit. It isn’t the first time Redzepi’s closed his iconic restaurant. He shuttered Noma in 2016, relocating his entire staff to Tulum for a lavish pop-up, before reimagining the restaurant in a new space in 2018.

“The style of fine dining that Noma helped create and promote around the globe — wildly innovative, labor-intensive and vastly expensive — may be undergoing a sustainability crisis,” Julia Moskin reported for The New York Times. When Redzepi, one of the most highly decorated chefs in the world, is telling you that restaurant economics are broken, they’re really fucking broken.

“What this news signifies to me is a flashing warning sign for the end of global fine dining,” former Food & Wine Editor-in-Chief Dana Cowin told Bon Appetit, “If Redzepi can’t make it sustainable, who can?” The answer to that question of course is: Who cares? The food media has been scrambling to understand if Noma’s closure is sounding the death knell for high-end restaurants. But we should be worried that Redzepi’s decision portends something much worse — an existential crisis for dining itself.

It’s hard to feel sympathy for Redzepi, who’s been surfing the frothy waves of cheffy stardom for decades. Jaya Saxena wrote for Eater about the difficulty in mourning a restaurant that most of us will never visit. “I won’t be sad because the window is closing to eat reindeer brain custard,” she writes, “while worrying I’d accidentally be too loud and ruin the near-holy experience some guests considered it.” Saxena gently reminds us that Noma never really existed for the proletariat. Redzepi’s restaurant and its luxurious forbearers, like Ferran Adrià’s El Bulli (which closed in 2011 after incurring massive losses), have pushed the envelope for creative cuisine, but they’ve also pushed it for extra-terrestrial prices. “Everything luxetarian is built on somebody’s back,” Finnish chef Kim Mikkola told the Times, “Somebody has to pay.”

Noma’s looming closure illustrates that even with affluent clientele, a massive waitlist, and a menu that costs as much as a round-trip ticket to Copenhagen, a restaurant’s balance sheet can still be in the red. Reporting for the Financial Times earlier this year, Imogen West-Knights unearthed some of the nasty secrets about how Redzepi has kept Noma afloat all these years. Her report details how Redzepi and other fine dining chefs rely on a steady supply of unpaid stagiaires to do hours of grunt work like assembling intricate edible beetles made from fruit leather, tasks that contribute little to their culinary education.

West-Knights writes:

“In fine-dining restaurants, two stories are being told. The first is in the dining room, a perfectly choreographed show of luxury and excellence, a performance so fine-tuned, down to the décor, the staff uniforms, the music, the crockery, that in some ways the food itself is the least important element. And then there is the story that you, as a diner, are never supposed to hear. The story of what happens on the other side of the kitchen wall.”

Redzepi didn’t create the stagiaire system, the French did (as Jeff Gordinier points out in a sympathetic essay for Esquire). But we should expect more from the chef of a “World’s Best Restaurant,” even if a post in Noma’s kitchen still carries enough currency to entice ambitious young cooks to work for Redzepi pro bono. Now that the curtain has been raised, however, these exploitative practices are harder to hide and impossible to justify.

Among the many things the dining public doesn’t understand about how restaurants work is the misconception that all busy restaurants are profitable. Being denied an 8pm reservation at one of your favorite places does not mean that the owner of the restaurant is making a killing. In fact, having a full dining room during prime-time hours is the bare minimum of what restaurants need to do to survive. People are so often flummoxed when their favorite places close. “It was always packed!” they’ll say. Somewhere, a Noma regular with a fat wallet is thinking the same thing.

As Saxena points out, though, dining at Noma has always been out of reach for most people. But its closure is still a cautionary tale, if not the canary in the coal mine that died of smoke inhalation. It’s easy to argue that there’s never been a more challenging time to own a restaurant business than in the past three years since the pandemic began. But Americans are adept at sweeping trauma under the rug when it helps clear the path for unimpeded commerce. We see what we want to see. When the price of eggs goes up a dollar, we don’t care to understand why. It’s our God-given, American right to complain about it.

All this makes it easy to forget that at the onset of the pandemic, over 100,000 restaurants in the United States closed overnight. Millions of hospitality workers lost their jobs, and many of the restaurants that employed them never reopened. Of course, we’ve come a long way since then in the rebuilding process, but the wounds haven’t even come close to healing. Most restaurants, without the cache of a world renown chef and a dedicated fermentation lab, have scars that run much deeper than Noma’s. But it’s always been in the industry’s DNA to conceal the chaos behind the curtain. We’re trained to absorb trauma ourselves, and we go to great lengths to shield our guests from the less glamorous aspects of operating a restaurant, including going broke.

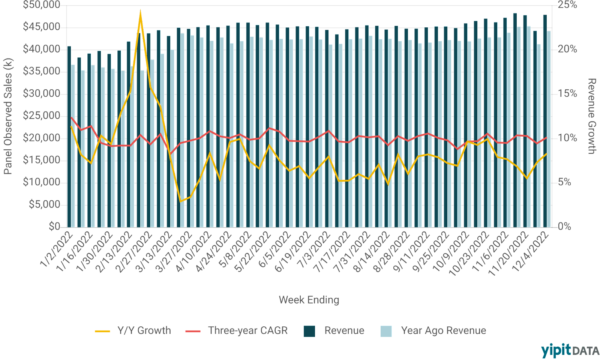

According to the POS company Toast in its Q2 Restaurant Trends Report issued last summer, restaurant sales have returned to pre-pandemic levels. However, a closer look at the trajectory of sales figures over the past few quarters shows revenues flatlining, which is a cause for concern for many small restaurant businesses. A more recent report from analytics firm YipitData shows that year-over-year restaurant sales growth decelerated throughout November, breaking its 3-month accelerating trend (see chart below). Independent restaurants are feeling the pressure. According to Nation’s Restaurant News, more than half of the country’s independent restaurant owners couldn’t pay their rent in December.

In the wake of the pandemic, Americans are ordering food delivery at a much faster clip which makes traditional brick and mortar businesses with dedicated space for in-house dining too expensive to operate. As a result, restaurant footprints are shrinking, and ghost kitchens are creating even more distance between us and the people cooking our food. The public treats restaurant delivery the same as it does cheap goods on Amazon — instant gratification, one click away. Aggregators like DoorDash and UberEats are designed to remove as much friction from the ordering process as possible. But these technology companies make terrible romantic partners. They’re parasitic by nature, lowering customer acquisition costs for small restaurants in exchange for exorbitant transaction fees.

The truth is that restaurant economics have been damaged for a long time, but the pandemic broke the spokes off the wheels. Demand for restaurant food has been durable, but input costs are skyrocketing, and price sensitivity is high. In most major cities, the startup costs to open a new restaurant create a barrier to entry that’s nearly insurmountable without deep-pocketed investors. This contributes to a non-virtuous cycle of privilege. Despite the widespread effects of social movements like MeToo and Black Lives Matter, the underlying economic forces still favor white male chefs and milquetoast corporate concepts.

But we shouldn’t be looking at restaurants like Noma or chefs like Redzepi for sustainable templates for longevity. No one can deny Redzepi’s influence in the culinary world. But he’s still dedicated most of his career to lathering up the rich with absurdly expensive, tweezered food. There’s never been anything sustainable about doing that for two decades, yet Redzepi is treated like a messianic figure by the food media.

One important thing Redzepi is telling us, however, that we should listen to is how physically and emotionally draining it is to run a restaurant. It’s a common feeling among restaurant owners across the world right now, but we’re too busy sulking about Noma to notice all the other bodies piling up. Andrew Zarro decided to close his coffee shop, Little Woodfords, in Portland, Maine, after coffee prices doubled. In his eyes, the hospitality industry never recovered from the pandemic and customers are in denial about the challenges that businesses like his are facing. “If something doesn’t happen to intervene,” Zarro told the Portland Phoenix, “we’re only going to have large-scale chains or franchises. Portland might end up looking like any other city in America.” While coffee shops like Little Woodfords are closing all over the country, the local Starbucks, likely, is not.

The dining public needs to start accepting the true cost of high-quality restaurant food and taking a more active role in helping foster a healthy restaurant landscape. This means patronizing restaurants that pay staff fairly and support the community. Consumers who buy cheap goods on Amazon every day can’t expect local businesses to flourish when they can’t compete with Amazon on price. It’s the same for buying $10 Chipotle burritos. We don’t get to have the mom-and-pop Mexican place that sells delicious burritos down the street, if we aren’t willing to pay $15 for one. Every Chipotle purchase is another nail in the independent restaurant’s coffin.

In some ways, we’re all responsible for the house of cards the restaurant industry has become. We shrug our shoulders when we walk by the shuttered store fronts of long-standing pillars of our community and get excited when they become Paneras and Chik-Fil-As. At the end of the day, the restaurants that surround us reflect our values and our communities. We’ve been selling our soul to the wrong kinds of restaurants for a long time, which makes life very difficult for the right ones. Meanwhile, our insatiable desire for on-demand food is poisoning the commercial landscape and reshaping the contours of Main Street U.S.A. The longer we ignore that, the more ghost kitchens will turn our city centers into ghost towns.