In her episode of Chef’s Table, Asma Khan, reflecting upon her success as a restaurateur, sums up her philosophies about hospitality by saying that “a guest is an incarnation of God.” She envisions her role as a chef beyond the kitchen—to deliver unconditional hospitality to her guests—devoting herself physically and spiritually to the people she feeds. Chef Kahn’s statement implies that a chef’s path toward achieving enlightenment is found through the joy of her guests.

Today’s diners expect transcendent restaurant experiences which has brought about a dramatic change in the way hospitality is administered. In extreme cases, a restaurant staff must faithfully commit itself to service in the way that some dedicate their lives to a set of religious beliefs. This quest for purity can make modern restaurant work an ascetic pursuit, where holiness can only be achieved through deprivation. Individuals that are incapable of achieving the level of piety necessary to please guests are defrocked.

In the most dogmatic restaurants, the idea of achieving salvation through hospitality can border on the occult. In reality, supplicating ourselves on a daily basis to serve others exacts an immeasurable psychological toll. Restaurant work is already hazardous, mentally and physically, but being expected to unconditionally love guests who often don’t reciprocate is toxic. We bend but don’t break, yet we cover up our bruises and convince ourselves that abuse comes with the territory.

One busy Saturday night at a former restaurant job, the staff was relieved to learn that the last reservation was a no-show. The line cooks—drenched in a combination of sweat and animal grease—began gradually breaking down their mise-en-place, as they do every night when they’re given the “all-in” signal from the host stand. There is a ritual to this denouement in busy restaurant kitchens. In the dining room, waiters mustered the necessary adrenaline to shepherd the last few tables to completion. The staff was exhausted, many had already been working for twelve hours straight.

Almost thirty minutes after the restaurant had officially closed, the no-show party materialized and, of course, expected to be seated. Many restaurants would have apologetically refused them a table but high-end restaurants, like this one, tend to be more charitable. The manager on duty scurried into the kitchen in a panic to plead with the attending sous chef to accommodate the latecomers. The morale of the staff deflated as the manager made the executive decision to seat the table.

The dining room was almost empty which meant that the entire staff would need to extend their work day by several more hours to care for one late table. In any other realm where appointments are compulsory—hair salon, doctor’s office, airline, theater—this group would have been denied service. Turning guests away in a restaurant, though, is an act of war—an affront to one of the basic tenets of hospitality.

Of course, we all put smiles on our faces and treated their party graciously, but the staff was incensed. Putting our feelings aside is part of the job in restaurants—it’s deeply ingrained in our DNA. But should we also be expected to put our well-being aside too? Is there a threshold where the welfare of our staff should be placed above the welfare of our guests?

Occasionally restaurateurs will defend their staff when guests are careless, but the vast majority take a passive approach in the face of impropriety. In hospitality, we’ve been programmed to always take the high road even when our guests’ behavior is beyond reproach. The high road is a one way street.

Every restaurant worker has witnessed countless tables of loud, inebriated businesspeople destroy the atmosphere of a restaurant with boorish behavior. Despite complaints from neighboring tables, management rarely intervenes to ameliorate the situation. The risk of offending the noisy table isn’t worth appeasing the others who are bothered by it, so we take a docile approach. We tolerate their behavior like bad parents, and they continue misbehaving like spoiled children.

Instead of asserting ourselves, we’re trained to “kill them with kindness,” even though most of these situations call for discipline. Part of the reason that people so confidently misbehave is because there is so little risk of being reprimanded. Poorly-mannered, paying guests often revel in their immunity.

We choose to pacify them because there is an unwritten Hippocratic-like oath in hospitality to which we pledge to adhere: Every guest must leave happy, even the ones who arrived miserable. Committed restaurant professionals take that responsibility very personally. But there is a hidden cost to our tolerance. The old tired tropes about how servers can “turn problem guests around” feel out of step with the times.

We inflict emotional damage on ourselves through the selflessness that service jobs require. Feelings of humility descend too easily into feelings of inferiority and the consequences are corrosive. The psychological baggage we carry around with us from our daily nightmare scenarios manifests itself in relationship problems, workplace harassment, excessive consumption of alcohol, drug abuse and insomnia. And, yet, we come to work everyday and are reminded that denigrating ourselves for the edification of others is the only path toward righteousness. It isn’t.

The emerging mental health crisis we face in the restaurant industry varies directly with the metastatic popularity of restaurants. The more seriously people take their dining experiences, the more emotional energy is required in the background to make those experiences successful. The harder we work, the more entitled our guests are becoming. As much as we wish we had more leverage, it will always be a buyer’s market.

We rarely look at some of the public scandals of abuse and harassment in the restaurant world and blame the culture as a whole. Of course, we must hold rogue individuals accountable for their behavior, but we cannot expect to stem the tide without addressing the underlying dysfunction in our industry.

The deep-seated problem lies in our subconscious belief—upheld by generations of restaurant professionals—that we are less important than our guests. Attempts at self-preservation are routinely met with proselytizing and hospitality jingoism. If you don’t like dealing with difficult people, find another line of work. (See: The comments section of this article for the inevitable backlash.)

The goal in hospitality is to make people happy, but should feeling responsible for other people’s misery also be considered part of the job? Restaurant guests have been conditioned that if they fuss enough, we will cower and meet their demands. We always negotiate with terrorists, and we concede too much because we’re afraid that if we don’t they’ll start killing hostages.

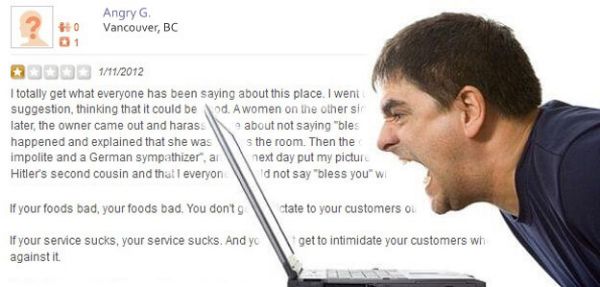

We need to start by decoupling our satisfaction from the satisfaction of our guests. As restaurant professionals, it’s possible for us to perform at a high level and still not convince our clientele of our greatness. If they don’t leave satisfied, we shouldn’t feel like we’ve failed. Too often, we tie our self-worth to external factors. We obsessively read online reviews, shoulder the burden of guest malpractice and stay silent when dissatisfied people sling mud at our reputation.

Industry leaders also need to be less rigid about what constitutes good service and more forgiving of their employees when guests are critical. Management should empower staff to stand their ground when confrontation arises. Why should servers have to run to tell mommy and daddy (the managers) every time they have a problem with a guest? Rules should be firm and apply to everyone. Ham-handed attempts to flout the rules should be unapologetically rebuffed.

Holding our guests to a higher standard has inherent risks but calling them out when they are disrespectful reminds them that we are equals and humanizes the transactional nature of hospitality. If—like Chef Kahn says—our guests are truly godlike, it shouldn’t be too much to expect for them, like God, to also be merciful. In the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Guest. Amen.