If you’re a responsible restaurant owner with a track record of treating your employees respectfully, let me apologize in advance. For the rest of you—too many to count—who’ve made your fortunes at the expense of your staff, don’t be surprised when your help-wanted ads go unanswered.

Finding qualified staff willing to work has emerged as one of the biggest challenges to recovery. As Coronavirus case loads decline and access to vaccines expands, consumer demand for dining out has grown, but the pool of restaurant workers, many who’ve been relying on unemployment benefits for months, has not.

Some hospitality professionals have abandoned the industry altogether. Months of waiting to return to their old jobs has left many workers worried about being left alone at the altar. Others chose to relocate to places where jobs are plentiful—cities like Miami where disruption to restaurant businesses has been ameliorated by more permissive public health policies.

In the early innings of the pandemic, Hanna Raskin of the Charleston Post and Courier reported on the staffing outlook in her home state and beyond. Among other silver linings, restaurant workers she interviewed celebrated having more time to spend with family, perfecting bread baking skills and enjoying the pleasures eating three meals a day at regular intervals (something a restaurant schedule never accommodates).

These anecdotes portrayed the pandemic as a desperately needed sabbatical for many former staff (even though most admit that they didn’t sign up for normal lives when they chose a restaurant career.) Even then, an owner touts his focus on making working conditions at his restaurant “so bearable” that staff won’t want to leave. But making working conditions more bearable is hardly an ambitious goal.

Media narratives are now predictably switching from suffering workers caught up in the maelstrom to victimized restaurateurs struggling to recruit staff. As it would be with any industry, it’s a false assumption that money is the only motivating factor for an entire industry’s workforce. Many workers are feeling restless. Others have lost faith in the industry as a viable career path.

Even with vaccines on the rise, restaurant workers are still among the most vulnerable to contracting the virus at work. Some individuals who’ve lost their jobs also lost their heath insurance coverage during the worst public health crisis in a generation. When the industry shut down, many owners immediately laid off their entire staff, no questions asked, even their most loyal workers.

The assumption that the attractiveness of unemployment benefits is causing labor shortage is an oversimplification. But restaurant workers are accustomed to being blamed for things that aren’t our fault. We’re trained to feel responsible for failures even when we ought not be—by people that are disappointed with their food when they didn’t understand what they were ordering; by large parties that arrive over an hour late for their reservation and are refused a table; or just by average run-of-the-mill miserable patrons who will themselves into having a miserable experience for which we, in turn, are expected to shoulder the guilt.

Meanwhile, in the name of hospitality, ownership and management continually elevate the status of guests above the status of their employees, cowering to guests regardless of whether their complaints have merit. They obsess over the staff’s failures without celebrating its successes. They’ll say it’s tough love, but many restaurant workers now realize that tough love is the only kind of love the industry has to offer.

So, why should restaurant workers feel compelled to help carry the burden for a struggling industry that so often took them for granted when times were good? Many owners are now learning the hard way that the labor market will dry up if they cannot attract workers with better wages. Some are even offering cash bonuses up front to onboard new employees.

A recent article in the Washington City Paper by Laura Hayes offers a measured analysis of what’s behind the labor issue in the current climate. One server describes feeling abandoned. She says, “It left us feeling like if this happened again, we can’t trust that we would be taken care of. We’re not considered essential except by people who don’t want to cook.”

Fear of contracting Covid-19 is still high on the list of reasons restaurant workers are opting out. For the moment, there is no organized way to verify whether guests have received the vaccine—and there likely never will be—which puts workers at even further at risk. With new variants emerging and a significant percentage of the population refusing to be vaccinated, indoor dining can still be counted among the most dangerous vectors for contagion.

As Ms. Hayes’ article indicates, many workers don’t trust management to implement and enforce proper protocols and to prioritize safety of staff. Over the last decade, there have been hundreds, if not thousands, of wage theft lawsuits and well-publicized harassment allegations. Restaurants owners, by and large, have an undistinguished record when it comes to taking care of their workers. It’s no wonder that so many workers are apprehensive about reconciliation.

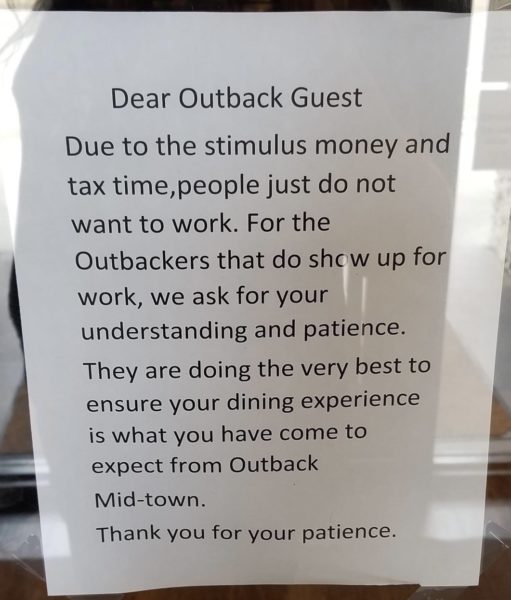

This past week, a manager of an Outback Steakhouse in Memphis posted a makeshift sign on the entrance blaming their staffing issues on people’s unwillingness to return to work because of stimulus money. The company apologized on social media and the sign was removed, but the public shaming of former staff members points to a deeper cultural problem endemic to the hospitality industry. Staff are too often subjected to this kind of unwarranted contempt.

There’s more to workers’ reticence about rejoining the workforce than a stimulus check. Returning to work brings with it a whole new set of challenges: inconsistent scheduling, unpredictable income, and the possibility that capacity restrictions or lockdowns may be reinstated.

The jobs that restaurant workers are being asked to return to aren’t the same jobs. Staff are now tasked with policing masking, moving heavy furniture to configure outdoor dining, and packaging to-go orders. Imagine if you were furloughed from your job then offered it back with more responsibility and less pay; you probably wouldn’t be in a hurry to return to that job either.

Few restaurant businesses, especially smaller independently-run ones, offer health insurance or retirement benefits to their hourly employees. In many cases, laid off workers became eligible for cost-free or affordable health care via the ACA marketplace. Returning to work would risk forfeiting those government subsidies and likely make insuring oneself impossible on a modest restaurant salary.

The generational sociological issues that have bubbled to the surface in recent years—MeToo, Black Lives Matter, AAPI Hate—have made it impossible to hide the skeletons in so many restaurant closets. This weighs heavily on the collective consciousness of the industry and is making returning to normalcy a feeble aspiration.

Earning a living by catering to the needs of rich, mostly white people in fancy restaurants requires a tamping down of one’s own social consciousness. The choices that restaurant workers today are making about whether or not to stay in the industry must be seen through the prism of these tectonic shifts that have defined the pandemic era.

Restaurant owners will need to offer more incentives to attract quality workers and foster healthier workplaces. This means running their businesses in a way that demonstrates a deeper commitment to gender equity and racial justice. Hospitality careers will not be as attractive in the near term, which puts the onus on restaurateurs to treat their staff better and pay them more, a lesson they should’ve learned a long time ago. But as they say: Sometimes you never know what you had until you’ve lost it.